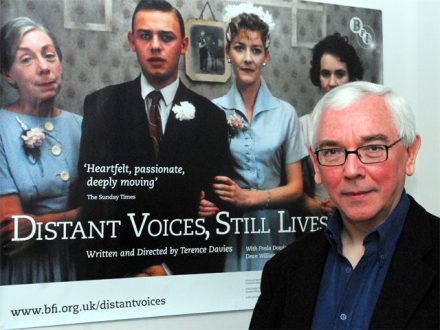

There are few voices in cinema so singular and charismatic, yet built on such a small filmography, as that of U.K. director Terence Davies. He initially came to prominence on the back of a collection of short films (repackaged as The Terence Davies Trilogy) depicting life in working-class Liverpool, where Davies himself was raised as one of 10 children, seven of whom survived. His masterstrokes Distant Voices, Still Lives and The Long Day Closes further analysed the openly gay director’s formative years — the former a look at his life as a low-paid clerk desperate for escape, and the latter glancing even further back to his childhood remembrances, his earliest sexual awakenings among them.

“At the time, the climate in Britain was more open than it is now. Both the British Film Institute production board and Channel 4 were very adventurous then,” says Davies from his home in London. “I returned to my life in that way, because after Distant Voices, there was still another story to be told.”

Yet, attempt to credit Davies with (in at least some quietly patient way) revolutionizing queer cinema, and he pays little heed to the idea. “I wouldn’t know, because I don’t watch it. Either I get depressed because the men are far too good-looking, or it just becomes homoeroticism, and I find that very boring,” he says.

Since 1992, however, several of Davies’s projects have fallen through, and in the ensuing 15 years his name has graced screens only twice more — first with 1995’s The Neon Bible, based on John Kennedy Toole’s novel, and then with 2000’s Edith Wharton adaptation The House of Mirth. “You reach a point in middle age where you can’t get work, and it’s no fun,” he says. “It’s increasingly difficult in this country if you have any voice that’s even mildly original. You can literally starve.”

Davies’s concerns for his homeland’s culture as a whole run even deeper than just a lack of support for artists. “What’s happening in Britain is not just in cinema, but political as well. We are now virtually another state of the American union. We imbibe everything from America. I’m not anti-American, but if we don’t stop it we’ll just be Hawaii with lousy weather,” he says.

“We’re constantly looking to America for validation, and so we imitate, yet imitations are always second-rate. We’re not Hollywood — we do Hollywood on the cheap and do it horribly. Who with any intelligence can sit through the original CSI? Why on Earth would you want to try and remake it?” he asks.

The solution for maintaining an English identity in the face of American culture isn’t easy. For Davies, “it’s important that we keep our own culture. The other cultures in Europe are protected by not having the [English] language. And unfortunately, we aren’t separated by a language and now it’s becoming frightening.”

As for cinema, Davies’s impressions run just as dour. “We’ve got 25-year-olds who think cinema started when Tarantino came along, and that it’s just an extension of television,” he says. “If that were so, we’d never stage Chekhov again, because on the surface nothing happens in Chekhov. But everything happens in Chekhov when it comes to the human condition and comedy. I don’t go to the cinema very often now, because I can’t actually suspend my disbelief anymore. Most of the time, you just sit through this stuff and you think, ‘90 minutes — my God!’ When I was younger, once the curtains went back and the lights came down, I was so excited.”

Re-assuringly, Davies continues pushing forward. While working through the finishing touches of a commissioned documentary on Liverpool (in celebration of that city’s placement as the European Capital of Culture this year), he’s also looking forward. “At the moment, my producer is trying to raise the finance for the next one I want to do called Mad About the Boy which — are you sitting down? — is a comedy with a happy ending. It’s set in a fashion magazine and takes place in London and Paris,” he says, and at least once in our conversation, the voice on the end of the line sparkles.